EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

At the core of health care is the patient and the delivery of services that make them feel safe, comfortable and ultimately result in improvements to their medical situation. The overwhelming emotional driver of the health workforce is to help people in some capacity.

However, for many patients the health care experience is challenging, bewildering and inconsistent. Forms go missing, waiting times are extended, treatments are long and painful and most interactions are compounded by the sense of the unknown, fear, trepidation and uncertainty.

From the provider side, the problems are augmented by workflow interruption from system changes or cumbersome legacy systems, increasing demand in the face of shrinking budgets and an overstretched workforce that is not always enabled to perform at their best.

Patient Journey Mapping allows an organisation to reconfigure their resourcing and approach to care, based on the experience of the patient, documented through the patient’s perspective. Not only is it a useful tool to promote better health care outcomes, it is also a powerful approach and mode of thinking that enable staff to uncover opportunities for improvement and innovation within their own work context.

This paper discusses the concept of the patient experience in health care and how journey mapping can be applied within a difficult, complex and ever-changing environment to improve efficiency, effectiveness and accuracy of care delivery.

Its success requires endorsement from the highest level, ensuring that staff are enabled to learn about the process and its power and see their ideas and initiatives implemented in the workplace. By embracing the process, health care organisations can make substantial improvements to care outcomes and financial performance

INTRODUCTION

The process of journey mapping has developed over a number of decades, originally through the lens of the customer lifecycle. The initial focus was on the relationship between customer and brand from their first interaction onwards. With this came an emphasis on the emotional drivers of the engagements, ensuring that customers received ‘positive’ brand experiences, thus creating a propensity to repeat a purchase. (Williams, I. 2015)

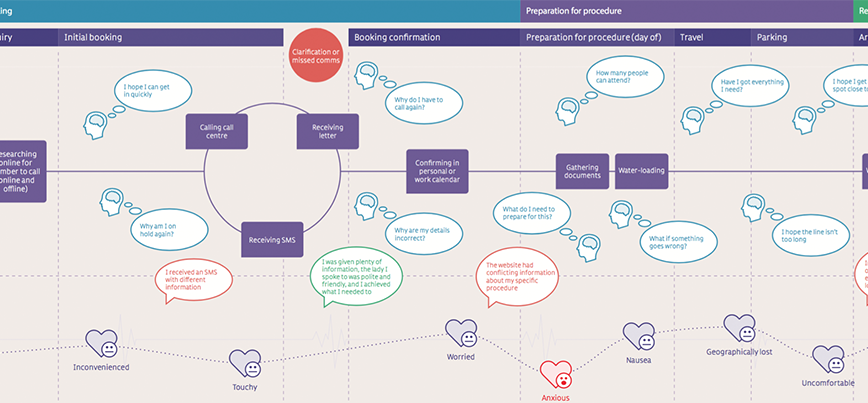

Within the last fifteen years the field of customer experience has emerged and with that, patient experience. Customer experience broadly highlights touchpoints with a brand through the perspective of the customer — what they think, feel, say and do. Moving beyond that enables an organisation to use this process to uncover the major pain points (e.g. what are we doing poorly or that does not meet the customer expectation) and opportunities (e.g. how do we improve/resolve the pains or create experiences that exceed the customer expectation). The end of this process is a set of initiatives that drive improvements to the customer experience, often prioritised according to impact versus effort.

JOURNEY VS PROCESS

Only within the last decade have these tools been applied in health care (with the British Medical Journal describing the process as ‘new’ in 2010). Even in those early stages, the initial discussion involved a “process map”, i.e. allowing an organisation to “see” and understand the patient experience by breaking down the management of a condition or treatment into a series of steps. These steps could be activities, interactions or interventions that ultimately created the patient pathway or process of care. (BMJ 2010;341:c4078)

While this is an important first step, a journey map is not a process map. The two should run in parallel but ‘process’ focuses on actions undertaken by a business and ‘journey’ focuses on either the current experience or the ideal / future state experience of the patient.

To contrast the two: from the patient’s point of view, they are not concerned about how many members of a hospital staff need to check and sign a discharge statement. They want to know they can leave the hospital in a timely and comfortable manner. The process needs to be efficient, accurate and meet hospital standards (identified and improved through a process map), but the customer simply wants to know that everything has been done and feel satisfied with the outcome, or be able to ask a question, if they still feel unsure (identified through a journey map).

While it is an easy and obvious contrast of the two approaches, this difference in thinking is reflected in business priorities and improvements. From a process point of view, the hospital may choose to implement a wide scale, high cost, high impact patient record system that deals with discharge statements. That comes fraught with long time frames, change management issues and staff disengagement, resulting often in poorly implemented systems or a lack of wide adoption throughout the organisation.

From a journey point of view, it may be identified that patients could create a digital signature that is signed via a docked iPad at the end of their visit accompanied by an (optional) written or auditory summary of what the hospital does next and whether they should expect any follow up. The patient can be informed and be enabled to seek more information should they want it. Otherwise they will exit the hospital and return to their daily life.

To contrast the outcomes, the latter appears easier to achieve and also provides meaningful patient experience data — e.g. if patients are repeatedly asking for more information (either written or spoken) is there an opportunity to start providing that information earlier in the journey?

It also creates consistency of records so in the future there is greater consistency of care. The impact on the patient is that they do not have to explain their health history again and are able to get to the issue faster. The impact on the organisation is that their staff do not have to chase up records or seek out missing paperwork. They are enabled to care more deeply for a greater number of people. However, the latter of the two is a microcosm of a much larger program of work. It is a bite-sized improvement that engages staff and creates a better experience for a patient.

There is a misconception that patient experience is largely a digital transformation effort. Or that it hinges on the IT department. The reality is that a patient experiences an organisation both online and in person, as patient and caregiver, and as part of or as the entirety of their day. While consumers (and thus patients) expect technology to ‘just work’, the patient experience highlights that every staff member from customer service, professional care and support services all strive to create a positive experience. And that infrastructure, whether a waiting room or an MRI machine, at the very least acknowledge the emotional state of the patient and do what’s possible to make them feel at ease. (Kayyali, B; et al, unknown publication date).

THE CHALLENGES OF THE PATIENT JOURNEY MAP

As a relatively new concept within health care, Patient Journey Maps are often viewed as too challenging, or too difficult to implement within current structures. However as tools and approaches have improved in others sectors, they can now be applied with greater ease within the context of health care.

One of the most challenging aspects of Patient Journey Mapping is that everyone experiences health care in their own way. Seeking to create truly unique experiences may be a step too far. However, for the purposes of identifying the bigger pains and opportunities, it is often easier to break your patients down into a similar or like-minded individuals, who are experiencing care in a similar way.

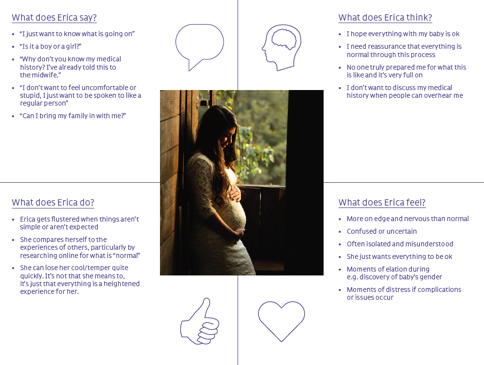

This may be done through customer segmentation, however the format that resonates more within the health care setting is that of “personas”. These are not as scientific as segmentation but provide a common sense approach to defining profiles of the most common types of patients, and other associated caregivers. It seeks more human characteristics — who they are by age, gender and background, what they care about, what motivates them and what they will generally say, feel and do throughout their interactions with an organisation. (Jones, P. 2013)

Implementing personas within a health care setting also helps normalise some of the language that patients may find challenging. It allows staff to think from the other side and describe issues in plain language without being bogged down by clinical vernacular.

Similarly, it is easier to engage with ‘Charlie the cancer sufferer” than it is to interpret the latest set of medical statistics. Personas are the method by which staff can find ways to create a greater level of care for Charlie rather than trying to reduce the readmission rates. It taps into the emotion of the staff themselves — to find ways to care for people, but it is done within a hypothetical situation that frees them from everyday process.

Another challenge of the Patient Journey Map approach is skepticism towards outside views or people who do not truly understand the work environment coming in and suggest things that could never be implemented. However, where this approach excels is by engaging staff across all areas of the organisation to understand, empathise with and ultimately improve and own the persona (and therefore patient) experience. Furthermore, it provides the organisation with opportunities for quick wins, so staff can see their ideas implemented in the workplace. This leads to a greater sense of ownership and a mindset shift towards quick, important and implementable improvements.

THE BENEFITS OF THE PATIENT JOURNEY MAP

There are several benefits to utilising Patient Journey Maps, particularly when leveraging “voice of the patient” tools to guide appropriate actions.

- Continuous care – Patient referrals outside of primary care providers often leads to a breakdown in communication. This may be due to technology, geography or other circumstances. This is one of the biggest issues that patients highlight and from their perspective, there are gaps in care, which affect overall outcomes and have financial implications.

- Better communications – Negative patient interactions are often the result of poor or inconsistent communications. If the patient has an expectation that is not met (i.e. the manner, tone or language of a care provider) it creates a negative outcome. Identifying when these are most likely to occur will create better efficiencies for practices.

- Continuous improvement – The ability to collect and use patient journey data is important to instil a culture of continuous improvement. Achieved by creating plans to review the data and leverage it to highlight systemic themes, recurring issues and other opportunities.

- Reducing or removing silos – Blind spots in care occur anywhere from scheduling to discharge, or point-of-care to follow up. This is often a result of workflow issues. By identifying these blind spots, improvements can be made to support and improve the patient experience.

- Educating patients – Many health related interactions leave a patient with a feeling of “what’s next?” This is often enhanced by feelings of fear or uncertainty. Being clearer and guiding the patient through the next phases of care leads to greater adherence to a care plan and fewer return visits or readmissions.

- Reducing pain points – There will be areas of care that stand out negatively in the mind of the patient. Better understanding of these points can help organisations to reduce or remove the negative events and identify more opportunities for improvement.

- Increasing emotional connections – At their core, care providers are empathetic and want to help others. Understanding a patient journey can highlight the associated emotions and create more opportunities to connect with patients on the right level. This promotes feelings of safety and wellbeing throughout the whole journey.

While a lot of these benefits may be considered ‘soft’, they do impact the staffing and resourcing of an organisation and their financial returns. Better patient experiences lead to fewer readmissions, better utilisation of space, fewer administrative issues and improved referral pathways. The economic benefits are dependent on the funding model of the organisation however in very simple terms, doing things more efficiently, effectively and accurately leads to better outcomes. (Cavallo, M. 2015)

PATIENT JOURNEY MAPS IN THE REAL WORLD

While the theoretical benefits of Patient Journey Mapping are easy to articulate, there are many real world examples of care improvement and financial performance by organisations that have utilised the process and committed to implementing the outcomes.

As described in a late 2013 presentation, the Mayo Clinic began implementing this process earlier that year. There were four components used to design patient-centric experiences:

- Patient Journey Maps to understand different mental states across the healthcare experience

- Behavior Mapping charts to cross-reference user state with needs

- Multi-user schematics to map out goals across audiences

- Mobile Wellness assessment to focus the information delivery to patients

(Senior, J. 2013)

Each area worked to help Mayo Clinic empathise with patients to develop the right design for their needs. They have been able to create experiences that are seamless, secure, accessible and even enjoyable by working internally to understand their patients on a deeper level.

Deloitte conducted exhaustive research on the relationship between patient experience and financial performance of hospitals. The results showed that “Hospitals with “excellent” HCAHPS patient ratings between 2008 and 2014 had a net margin of 4.7 per cent, on average, as compared to just 1.8 per cent for hospitals with “low” ratings.” (Betts, D; et al. 2016).

A two-year study conducted by Jessica Greene of George Washington University’s School of Nursing found that “patients with higher levels of activation demonstrated nine out of 13 improved healthcare outcomes. Comparatively, lower activation levels were associated with significantly reduced chances of positive outcomes for seven of 13 measures compared to patients who remained at level four (the highest activation level).” (Greene, J; et al. 2013)

CONCLUSION

By better understanding the patient experience through the use of Patient Journey Maps, health care organisations can make substantial improvements to care outcomes and financial performance. Similarly, organisations can improve staff satisfaction and engagement through their inclusion in the generation and implementation of the ideas and opportunities uncovered throughout the process.

This process can be implemented by organisations of all sizes, funding models and care delivery methods. It is equally as beneficial to a dentist as a radiologist, surgeon or midwife. An organisation will benefit if leadership commits to seeing the process through and to implementing the outcomes that will ultimately benefit the patient.

This white paper was originally published for w3.digital.

REFERENCES

Betts, D; Balan-Cohen; A, Shukla, M; Kumar, N (2016). The value of patient experience Hospitals with better patient-reported experience perform better financially. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/tr/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/lchs-the-value-of-patient-experience.pdf

Cavallo, M (2015, August 15) 3 Reasons Patient Journey Mapping Increases Efficiencies and Outcomes for Providers. Retrieved from https://www.careexperience.com/3-reasons-patient-journey-mapping-increase-efficiencies/

Cavallo, M (2015, August 8) 4 Reasons Your Patients will Benefit from Journey Maps. Retrieved from https://www.careexperience.com/4-reasons-patients-will-benefit-journey-maps/

Greene, J; Hibbard, J; Sacks R; Overton, V (2013, July) When Seeing The Same Physician, Highly Activated Patients Have Better Care Experiences Than Less Activated Patients. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1409

Jones, P (2013, pp77) Design for Care: Innovating Healthcare Experience. Rosenfield Media, USA

Kayyali, B; Kelly, S; Pawar; M (unknown). Why digital transformation should be a strategic priority for health insurers. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/why-digital-transformation-should-be-a-strategic-priority-for-health-insurersSenior, J (2013). Delight 2013: James Oliver Senior of Mayo Clinic on Experience Design in Healthcare. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66UtzLdcio8

Trebble, T; Hansi, N; Hydes, T; Smith, M; Baker, M (2010, August 13). Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/341/bmj.c4078

Williams, I (2015, November 16) Customer Journey Mapping – an art or a science? Part 1. Retrieved from https://customerthink.com/customer-journey-mapping-an-art-or-a-science-part-1/