2021 was a strange year. And I cannot blame it all on COVID either. Having been made redundant and then moving on within a week into a job where I ended up essentially feeling worthless, had a big impact on my professional psyche. And all this was a little over a year since I’d started to build back my own confidence — the transition out of agency life and into something else had been rocky at best and soul crushing on the daily.

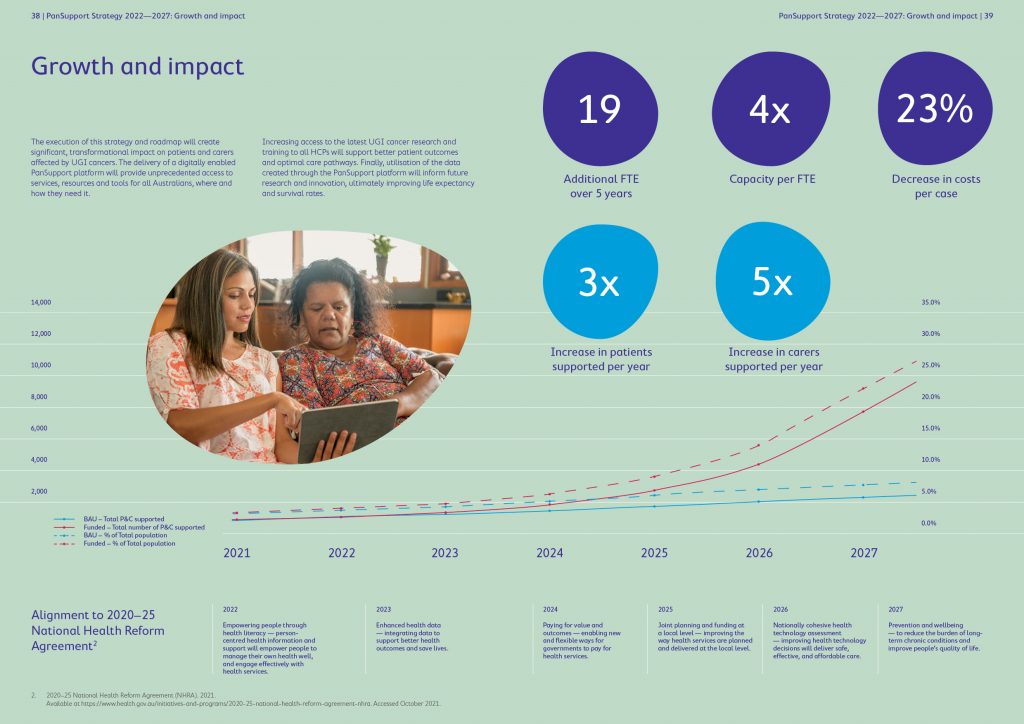

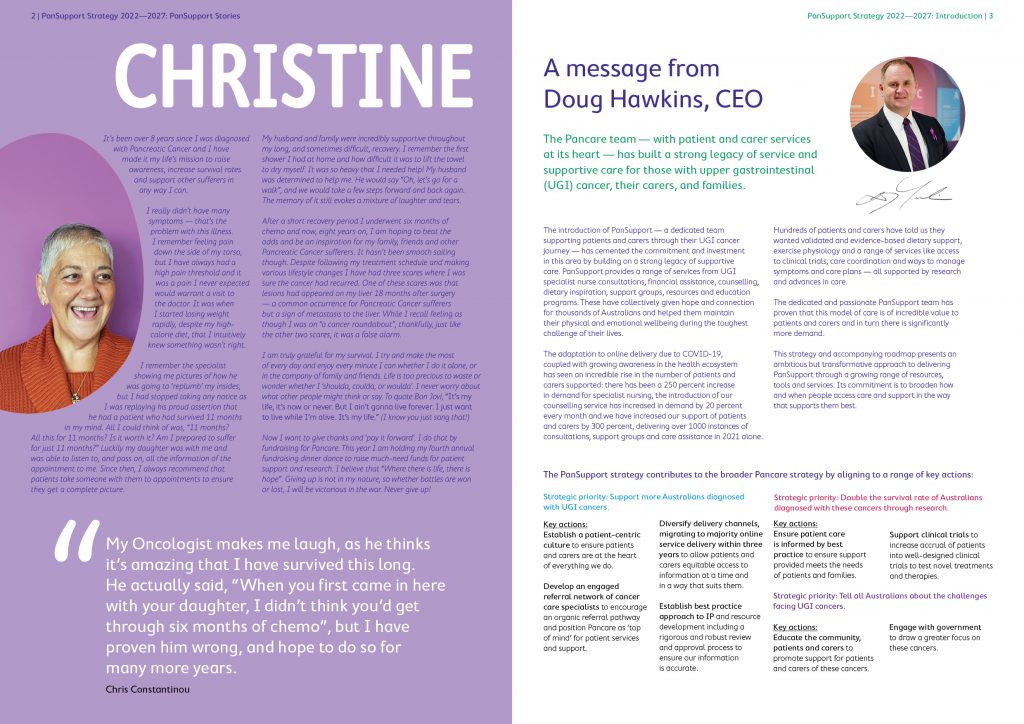

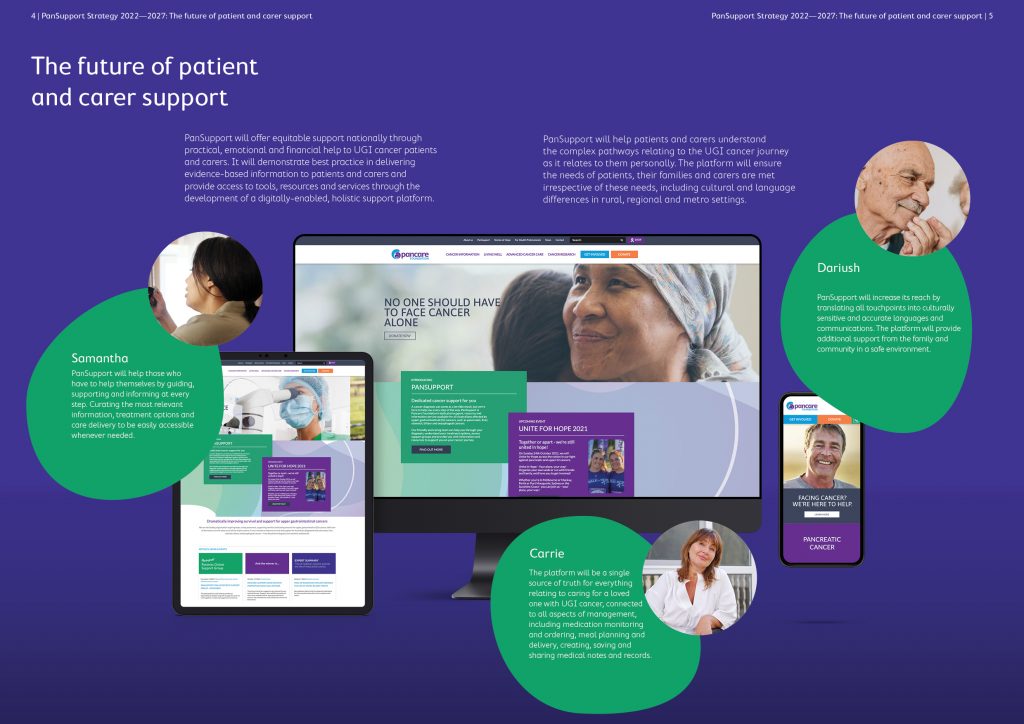

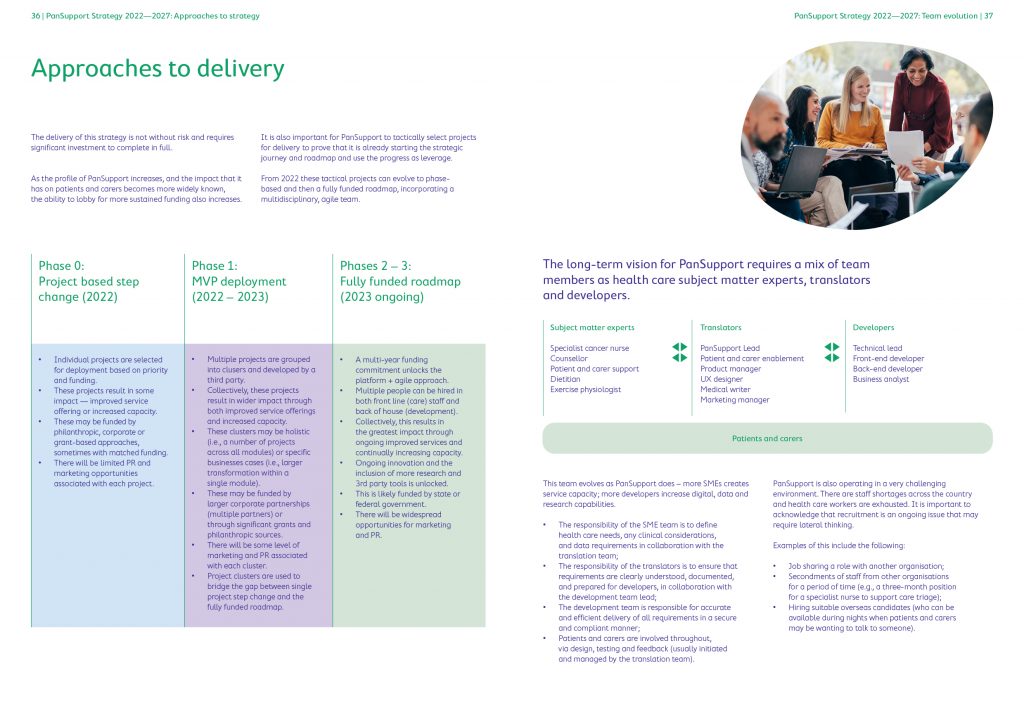

Still, opportunities present themselves and timing sometimes lands on your side. Through a combination of these things and because of multiple conversations, a bit of shared risk and a pretty compelling problem to solve, within a short time I found myself on the doorstep of the Pancare Foundation, tasked with creating a five-year roadmap for their patient and carer support services (PanSupport).

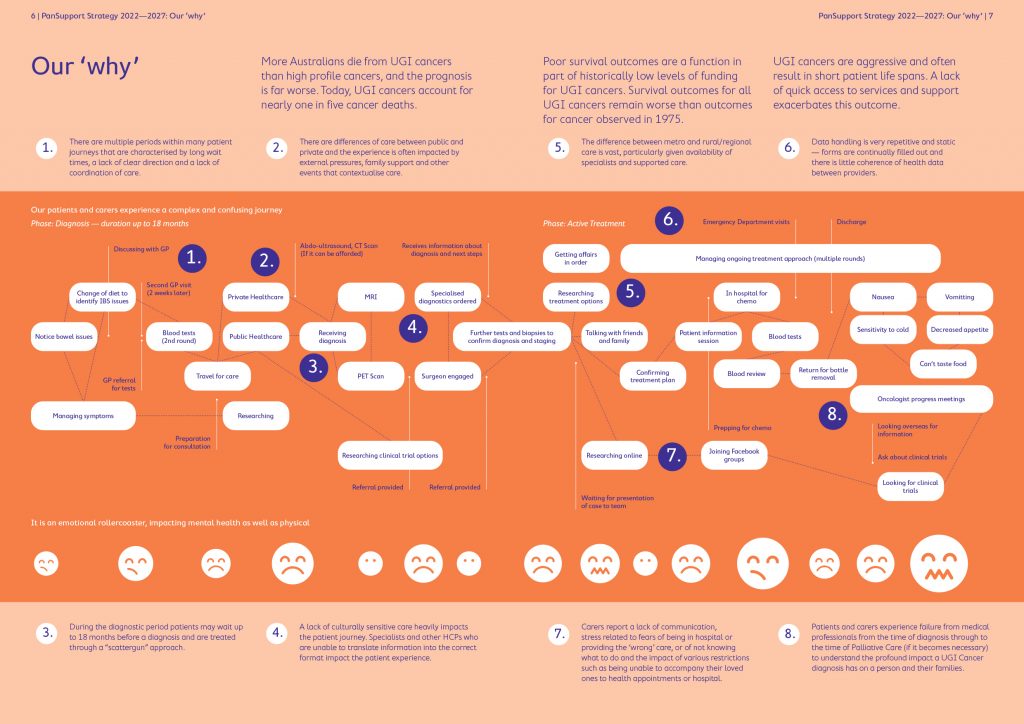

At the time, upper gastrointestinal cancers were not something I knew much about. What I could understand though were the deliverables of the project (even if they were ambiguous to a degree), as well as the impact my work could have. What got me across the line was the sheer discrepancy in funding for research into these types of cancers compared to more high-profile malignancies (e.g., 113mil for breast cancer vs 33mil over 5 years) and the survival rates (90+% vs closer to 10% for upper GI cancers respectively).

It is important to state that these statistical comparisons are not to downplay the incredible work that goes on in the fight against other cancers. It’s more the fact that it did not seem fair to me that these vicious cancers, that were almost always fatal, were so under funded that the outcomes had not changed in the last thirty years.

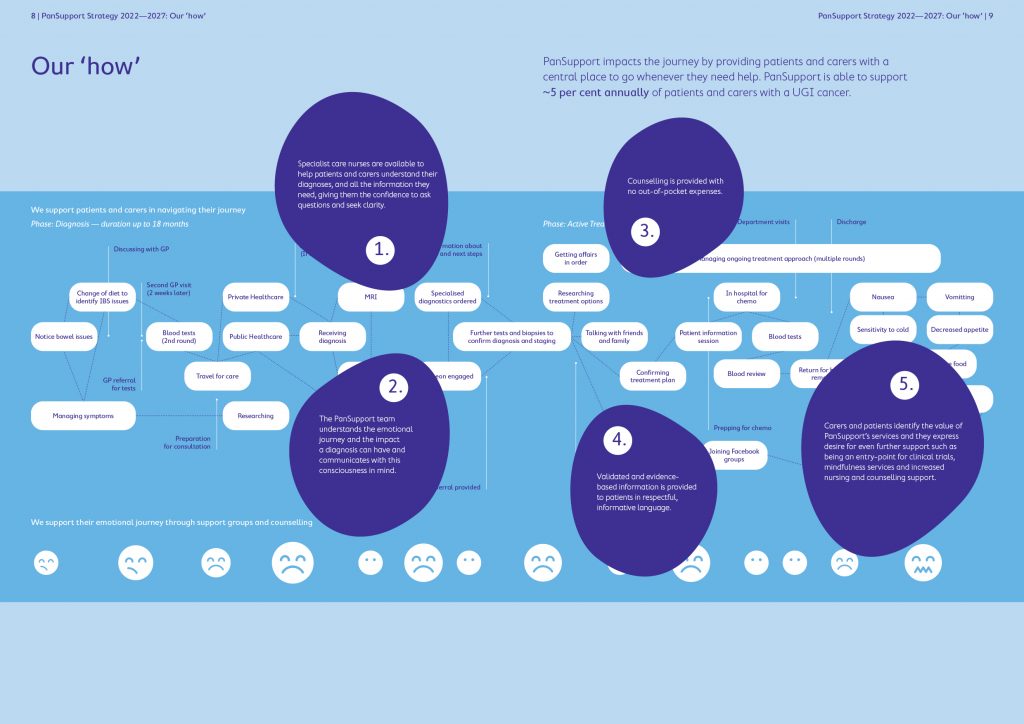

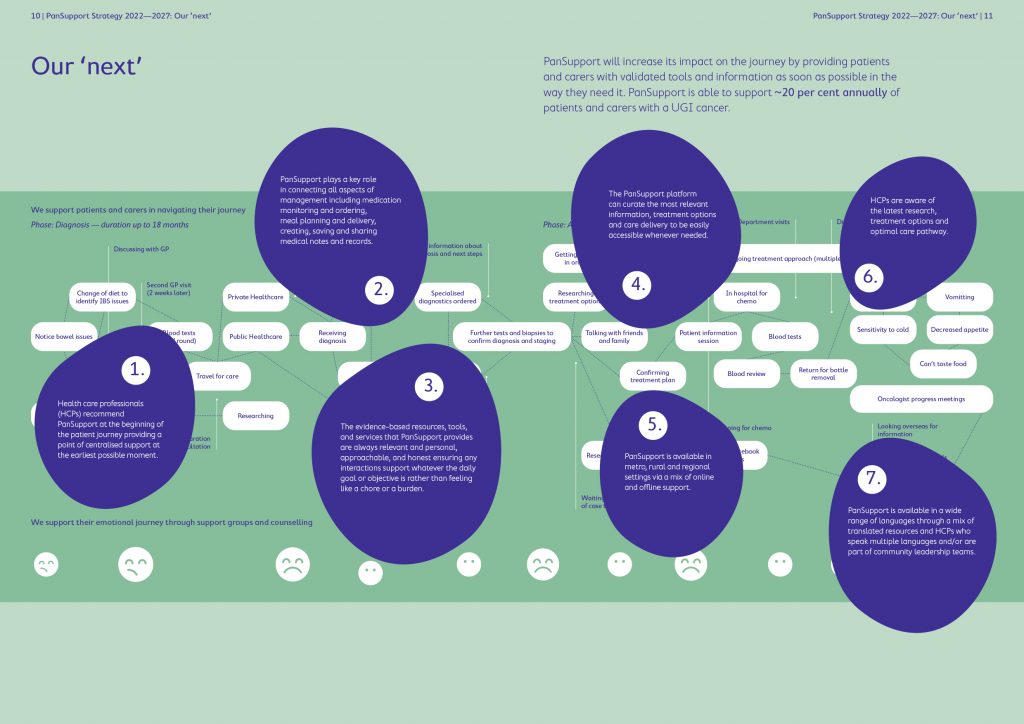

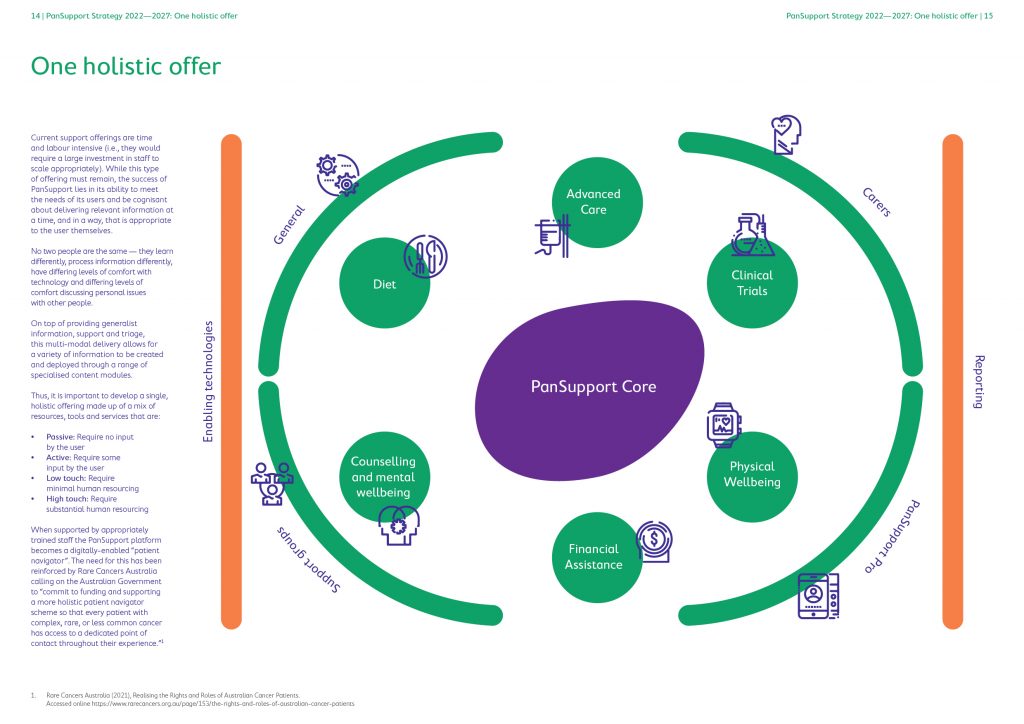

It did not seem fair to me that patients and carers were left to navigate a complex health care system and a lack of clear and distinct care pathways, compounded with an unimaginably emotional time with little to no external support. That is, until I learned about PanSupport.

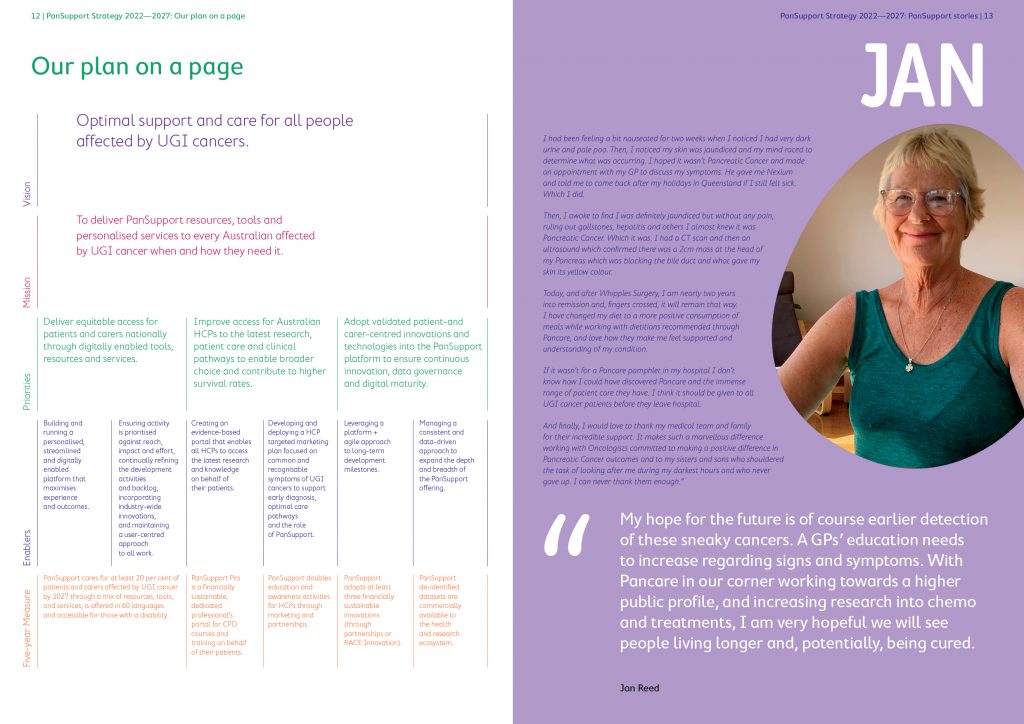

It’s easy to write about the work they do, and the impact their team creates. That could be a 5000-word blog without breaking a sweat. In fact, all combined I wrote over 35,000 words across a strategy and a roadmap. Two of the most dense, broad (yet detailed) pieces of work I have ever constructed.

Rather I’d like to focus on the things I learned through an eight-month journey, investigating some of the most emotionally challenging subject matters I’ve worked on, trying to make sense of complex and complicated experiences, working as a band of one while continually trying to get information and input from a team of people doing four times the work for half the pay.

A rigid process gets you rigid answers

I might be taking an unnecessary swipe at the broader world of consulting, but I’ve always felt like consulting groups have their “process” or their “method” and that’s a big part of their pitch. Very early on, I made the clear point that I did not have a specific process. My difference was to get in, learn about the problem and the current state of play and then bring whatever tools I had in my kit out to help chip away at an answer. I wasn’t (and am not) a square-box-square-hole type thinker. It doesn’t suit everyone and that’s ok.

As I started and begun to learn more, this resulted in many changes of approach and adjustments to my thinking, meaning where we landed was so far removed from my initial assumptions — but I can only hope this led to a better outcome because I did not force answers into specific frameworks. I started with what I knew and adjusted whenever something was challenged.

Having comfort with ambiguity has to come from the top

This process, or initial lack thereof, was really only acceptable because comfort with ambiguity was driven at a leadership level. It makes sense on face value to say you’re comfortable with ambiguity when dealing with upper GI cancers. It’s almost par for the course when every person you interact with is having a different and difficult experience.

But to live it in your everyday work life and to be given permission to explore the rabbit holes and the edges of the subject matter in aid of a better answer is something that rarely happens and it’s a credit to the whole Pancare leadership team. It wasn’t easy and it often meant work had to be redone but I truly believe that this mindset is one that leads to better outcomes, particularly as the path there is never straightforward.

Trust is earned through outputs and owning mistakes

I made a conscious choice in this project to share my work early and in as rough a state as possible. I wanted to take people on the journey of my thought process but mostly I wanted to be pulled up if my thinking was not resonating. The worst thing I could do was disappear for three months and come back with something that was completely misunderstood. Particularly as I didn’t have a team to bounce ideas off, I had to approach idea sharing as a form of feedback, even when it opened myself up to potential criticism.

I can look back on the multiple drafts (I counted 17 in all) and how rough the first couple were. But by doing so, I invited critique and comments, and raised questions that wouldn’t have otherwise been asked. I opened myself up by saying I didn’t know something, or I was just starting in an area, and actively sought input. I wanted every single person to feel like their fingerprints were on my work, as my role was merely a conductor and a curator.

Most answers exist if you provide the space for questions

Along the lines of being a conductor and curator, most of the information I was seeking existed somewhere already. If it didn’t, then the opportunity to ask questions was needed. Without stretching the imagination too far, I would guess that this is the case in many organisations. People often know the answer, or know how to find the answer, but they’re never given the opportunity or the prompt to do so. This freedom of exploration is often lost in the daily grind and overwhelming to-do list.

Ultimately what is needed is to find ways to explore ideas and look for answers and provide the space to play. I’m not sure if there’s a sure-fire way to resolve that need as part of a work culture. It has to suit the environment and the people. What is important to recognise is that developing problem-solving and lateral-thinking skills is something vitally important when there is no such thing as a clear or obvious answer.

At the heart of every challenge is a person

Over the course of the project, there was a pivotal moment where I could feel my work shift from something conceptual to something tangible. And that was after the first major journey mapping workshop where the whole Pancare staff worked with multiple personas to generate ideas to help and support them.

The initial work in developing personas reflecting patients, carers and healthcare professionals was a balance of raw data and creativity. Each one was crafted to tell a story that felt real but was not based on any one person. They incorporated interviews, surveys, and reports plus real-world insights. They took on a life of their own which was particularly strange when deciding which of our totally-made-up people would survive or not.

The aforementioned workshop was only successful because the real experiences of patients and carers were discussed to contextualise the journey maps. It was successful because the PanSupport team talked directly about what they deal with every single day.

It had a lasting effect on everyone who wasn’t on the coal face. The takeaway for me is that if you forget about the people you help, you lose sight of your ‘why’. And this is not the place to forget about your ‘why’ — too much is riding on it.

If an organisation believes in my capabilities, I’ll find the answer

This, as a reflection of where I started compared to where I am now, is the most selfish learning but the one I needed most. The last eight months has given me back the confidence I needed. I’ve developed and redeveloped a toolkit more advanced than I thought possible, I’ve tackled an area of patient experience so far beyond what I ever imagined, and I’ve led the creation of deeply impactful work that is already being picked up and used.

The biggest fear I had as a consultant was that my work would gather dust in a top drawer. Already I get to see day in, day out how much my work is informing the everyday strategy and projects. I get to see my work scare and excite people, which is exactly how I know it’s on the right track.

I can look at this strategy and roadmap and be immensely proud of what’s been created. It’s not too often you can truly hold something up as a piece of work that you think is your best to date, or a real indication of what you’re capable of. For me, this is one of those pieces.

It’s not enough to make me want to go back into consulting full time. It’s already enough to present new opportunities and subjects to tackle such that I’m not short of work in the near term. But the reality is I was actually part of a team committed to solving an important problem. It’s that environment that I want to get back to long term.

The more important and very real reality is that my work is a roadmap for how to help patients and carers right now, today and in the future.

It does not inform or impact the research that will lead to early diagnoses, earlier interventions, and better outcomes. That can only occur when proper funding is allocated over multiple years that is focused on clinical trials and novel therapies.

It’s time for the government to step up and do its bit. But in the meantime, ask around. It’s likely you’ll know someone who’s been impacted by one of these cancers. And donating to help PanSupport bring this roadmap to life will help thousands of Australian patients and carers. It may make that little bit of difference that someone needs, today.